Dynamic small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are the backbone of any economy, but are even more important in developing countries that don’t have so many very large corporations that employ thousands of people. Most companies of that type are headquartered in high-income economies, and serve global markets. In fact, many of the larger companies in developing countries are branches of those multinationals, serving the local market.

As noted in a previous post, there is a wide range of channels of finance for SMEs in high-income economies: banks, of course, but it is the complementary finance provided by nonbanks – finance companies and capital markets – that really enables young companies with promising market opportunities to realize their growth potential.

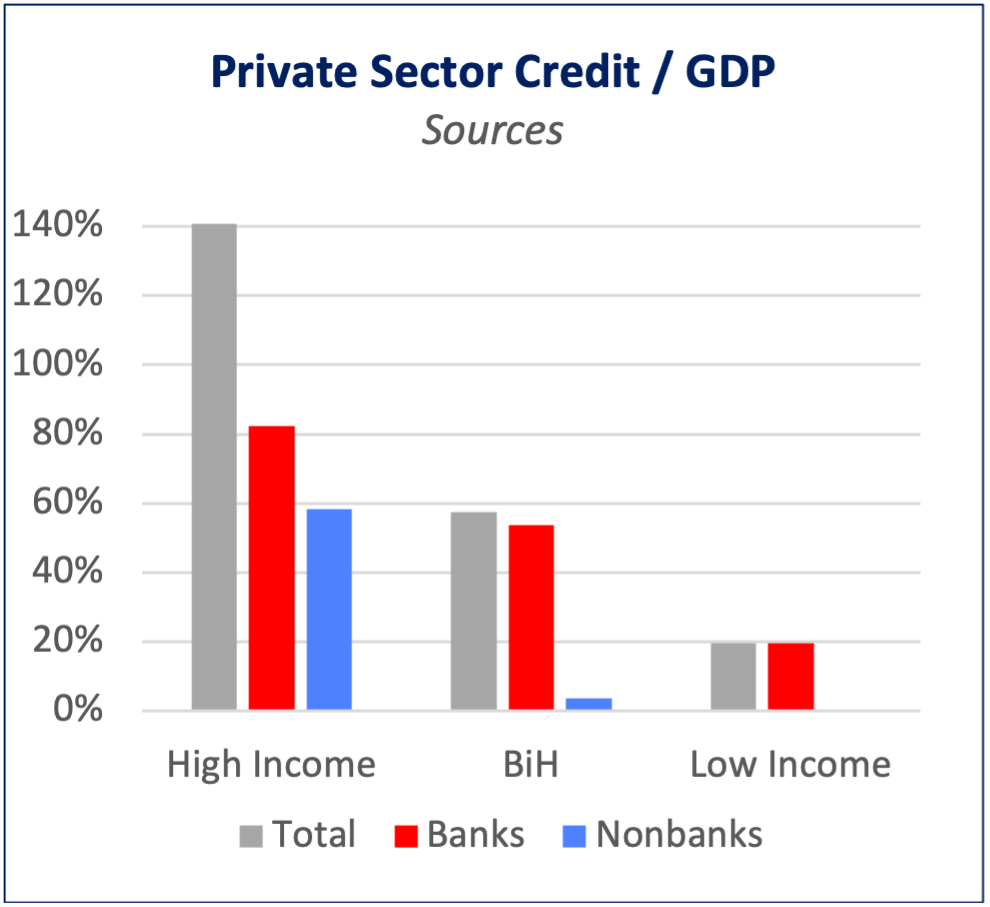

In developing economies, banks are not doing a bad job of providing credit to the business sector, as can be seen in the chart at right. It shows that the total private sector credit(PSC)-to-GDP ratio in high-income economies is about 140%, versus some 60% in Bosnia & Herzegovina, representing middle-income developing economies – a massive difference of 80 percentage points. Breaking that down as to source, however, the PSC/GDP ratio provided by banks is about 80% in the high-income countries, versus about 55% in BiH – a much smaller difference, 25 percentage points. The enormous shortfall in overall access to finance for companies in developing countries is not so much due to the banks. It is the near-complete absence of nonbank finance.

Furthermore, the majority of that bank finance in developing countries goes to the larger companies that are there, because they have well-established markets, professional business administrations, extensive real estate and equipment collateral, transparent financial records, and high-level relationships with bank officers. Typical SMEs don’t have much of that, especially those that are young and growing. Many are family businesses without sophisticated management structures. They may not have long histories. They don’t pull much weight with bank officers, who may have neither the time nor inclination to deeply understand SME markets. They often don’t have a lot of collateral, and once they have pledged that away for initial credits, their banks can’t really do more. And since they don’t have anywhere else to turn, because of the lack of nonbank finance, they have to wait. They can’t take advantage of the market opportunities in front of them, can’t compete, can’t realize their growth and employment potential. They wait, mark time, lose export opportunities to companies in economies with better access to finance.

The problem, then, for economic development, is stimulating the emergence of nonbank finance. As far as finance companies are concerned – leasing, factoring, purchase order finance, inventory finance, equipment finance – this is a difficult thing to do. Even though we have assisted countries in preparing the legal and regulatory groundwork for such operations, it is still up to the private sector to decide that there is enough profit opportunity to come in to a developing country and set up shop. Successes have been few. There are still significant gaps in the infrastructure of services supporting the financial sector, such as the absence of Dun&Bradstreet-like third party objective and credible company creditworthiness ratings that finance companies critically depend upon.

It is much more straightforward to begin to open up nonbank finance to the private sector though the capital market – in particular, through the establishment of investment funds providing growth finance to dynamic SMEs. Using Alternative Investment Fund law, along with some degree of risk mitigation provided by donors and local government, the design and launch of such funds is entirely feasible. Notably, departing from the usual practice of headquartering such funds in, say, Delaware or Luxembourg, they should be registered on local capital markets (which donors have spent considerable time and money helping countries set up properly), where they can pull in the excess liquidity that is typical of their banking systems, as well as funds from local high-net-worth investors. In addition, such funds are highly attractive to international finance institutions (IFC, EBRD), impact investors, and donor funds with development objectives, as well as commercial institutional investors seeking to expand into emerging markets.

To make a difference both in stimulating nonbank finance and in the volume of credit to the SME sector, we seek high volume. We are not interested in creating another venture capital-like fund, of which there are already quite a few, that will seek equity investment in a few deals per year, or funds that call a $10 million per year pharmaceutical in Yerevan an SME, and whose target deal size is $2-3 million. Our target market is the thousands of “classic” SMEs that are heart of the private sector of developing countries – those in the 25-75 employee range, mostly in light manufacturing and services such as IT and tourism, with annual revenues of $1-3 million, and average per-deal financing needs of $100-500,000. These are the “missing middle” still cited after all these years as lacking adequate access to finance.

For such companies, equity anyway is not the path to a high volume of deals, for two key reasons. First, there is no feasible equity exit, since most such SMEs are not expected to grow to the size that would interest a financial or strategic investor. Second, these are often family businesses, and parting with ownership is not of interest to them. Nevertheless, since the need is still for “risk capital”, the most appropriate financing instrument is the revenue term loan, where the yield to the fund is a combination of a low base interest rate and a royalty on revenues, enabling an equity-like return.

The paper linked below describes the feasibility of setting up such a fund in the Bosnia & Herzegovina case, but can be applied, adjusted for local regulations, to any developing country. It is the most doable and direct way to start getting nonbank finance to the private sector off the ground, for the benefit of the dynamic, “missing middle” SMEs that, by realizing their market potential, offer the greatest opportunity to accelerate a country’s overall economic growth.

Leave a comment